Cash-burning tech companies have been all over the news recently, with WeWork and its billion-dollar meltdown catching the most attention. The attention seems warranted, though. After all, how can a company such as WeWork be valued at US$47 billion as recently as January this year and now potentially be worth zero? Aside from the allegedly self-dealing CEO, Adam Neumann, who has been described as the “most talented grifter of our time,” WeWork raises doubts for private market tech companies and whether their business models are flawed.

This leads to an interesting question: How do you value a tech company that’s losing money? Recently, underperforming tech IPOs such as Uber, Lyft and Peloton have been dragged into the conversation with public investors questioning why they should pay so high of a valuation for a company that’s losing billions.

Your business model matters

Firstly, not all tech companies are the same. That seems pretty obvious, but there’s a wide variety of companies that are all lumped together in the same sentence at the moment.

Take Uber. Uber is a tech company that makes pretty advanced software connecting passengers and drivers worldwide. But Uber is losing billions of dollars each year (-US$8.289 billion in the last twelve months), as it competes with other ride-hailing services such as Lyft, Ola, Careem, Didi, and Taxify, on price, marketing, and driver incentives.

So, what does it take for Uber to become profitable?

Investors speculate it could take most of Uber’s competitors going out of business and potentially a future with driverless cars, so Uber doesn’t have to pay its drivers. That seems a pretty far-off future, considering Uber’s competitors are well funded too. People might also have an issue with Uber treating their employees unfairly in potential mass layoffs driven by automation. Investors will have to take a leap of faith.

Contrast this to the tech holy grail: the software as a service (SaaS) business. Zoom Video Communications, Cloudflare, and Slack — all of which recently IPO’d — are SaaS companies that are relatively early stage and growing fast. Cloudflare and Slack are not profitable yet, but it's not hard to see that they could become profitable soon. They could potentially be profitable right now, but they probably prioritise scaling their businesses.

SaaS businesses sell software to businesses. This is a profitable business model because selling software is very scalable — there aren't any additional costs for selling one more product — and businesses are generally good customers. Because SaaS companies sell software using a subscription sales model, their revenues are often considered by investors to be recurring and predictable (i.e. higher quality). Tech company heavyweights in the SaaS business include Microsoft and Adobe. Microsoft earned a bottom-line profit of US$10.7 billion in the quarter ending 30 September 2019, on revenue of US$33.1 billion.

Then there’s Beyond Meat. It’s probably not hard for Beyond Meat to turn a profit since it’s a company that makes money from selling its pea-protein patties to retailers and food chains. In fact, it just reported its first quarterly profit. However, Beyond Meat is not a tech company and it will probably earn similar margins to other food companies.

Valuing a high-growth company

Investors have been generously assigning value to these high growth companies based on their revenue and expected revenue growth, rather than profit. Even Wall Street analysts with their financial jargon and excel models often set their price targets for tech stocks based on a multiple of next year’s expected revenue.

Why do they do this?

For one, many of these businesses don’t make a profit, so revenue is all you have to base your projections on. Another reason could be that the profitable business model characteristics of SaaS and other tech business models, such as digital advertising, may lead investors to believe that these companies will have low costs and revenue will be similar to profit once they reach profitability and scale. The latter is clearly not true (see Microsoft), so profit being similar to revenue is likely a generous assumption.

It’s typical for a fast-growing SaaS company to be valued on 20-30x last year’s sales. These high-performance SaaS companies usually follow the Rule of 40, the principle that a software company’s combined growth rate and profit margin should exceed 40%. Zoom trades on ~39x last year’s sales. Is that price fair or stratospherically high?

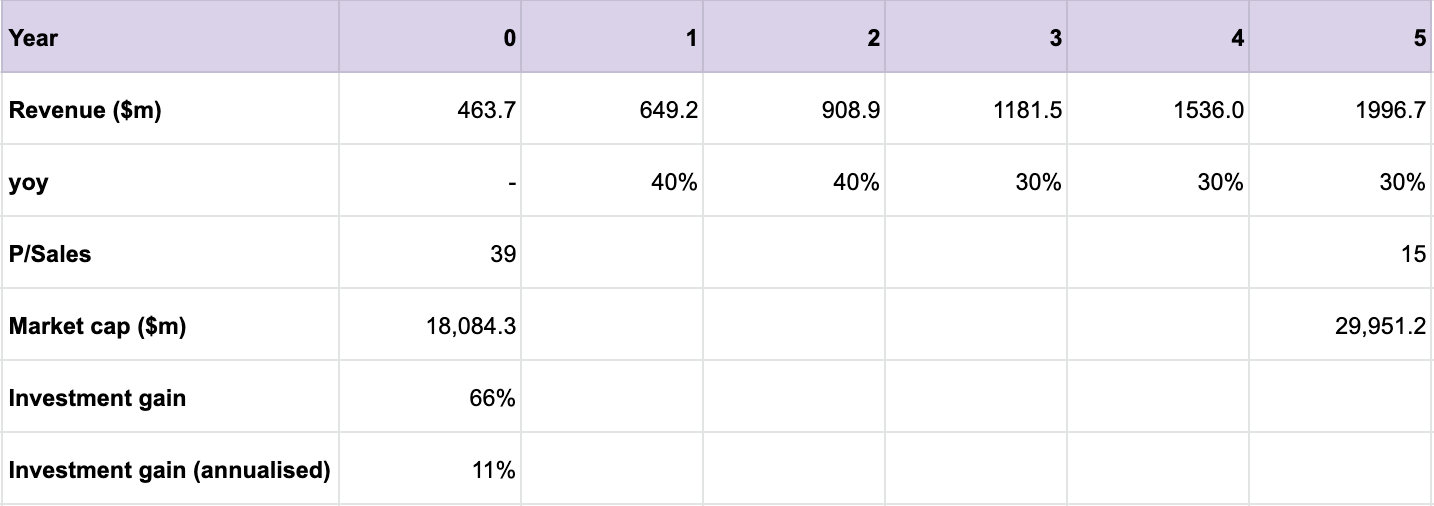

Let’s say Zoom was able to maintain its revenue growth at 40-30% for the next five years and its price/sales multiple fell to 15x. An investor would receive an annualised return of 11%.

It’s a big ask for a company to more than quadruple its revenues in five years. So, the return you receive is decent, but you could probably do better.

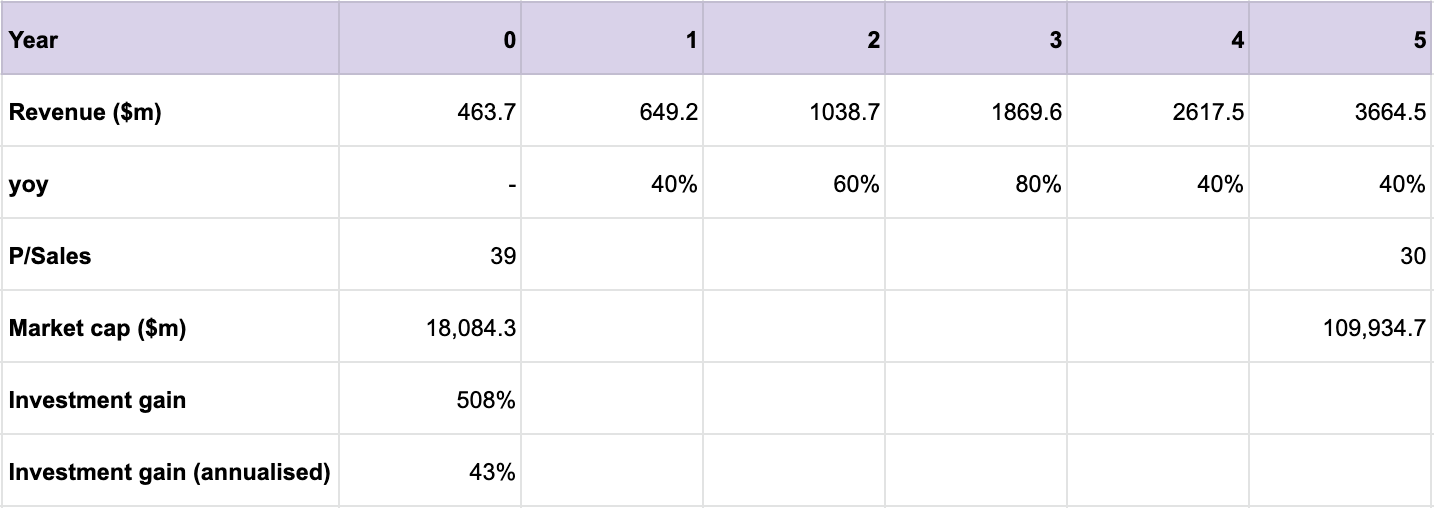

But it could turn into a great deal if Zoom continues to dominate in their field and becomes a behemoth like Salesforce or Adobe in the long run. Perhaps it’s feasible that Zoom can accelerate even further and grow its revenues more than seven-fold in five years? In this growth scenario, Zoom’s revenues grow to more than a third of what Adobe’s revenue was in 2018. Very few small SaaS companies can achieve this.

On the other hand, it could be a disaster for the investor if Zoom’s growth slows to 20% or 10% (which is still a very high growth rate for most companies).

This example shows there’s just a lot of uncertainty with valuing high-growth companies. For Zoom and other SaaS companies, it’s fair to say there’s a lot of growth priced in. That means despite these companies growing, there’s the risk investors won’t benefit if the company grows at a pace that is less than what’s expected.

The other risk is that the market stops valuing SaaS companies on a sales basis and starts to consider bottom-line profitability (or the lack of) more seriously. This would be brutal for stocks that can’t demonstrate that their SaaS business model can translate into huge, recurring profits.

Valuing high growth companies can be really confusing for individual investors and professional investors alike. You might want to buy shares in a company whose product you love, but you don’t want to overpay either.

Confusing Uber for SaaS

The problem is when tech companies that have capital intensive business models and non-recurring sales models are valued at SaaS revenue multiples.

It was reported last year that Uber wanted to go public at a US$120 billion valuation on US$11.3 billion of sales, effectively 10x trailing sales. After investors baulked at the valuation, Uber eventually went public with a US$82.4 billion market cap, closer to 7x trailing sales. As a point of comparison, customer relationship management SaaS company, Salesforce trades on 8.5x trailing sales and is profitable.

As of 15 November 2019, Uber stock has fallen ~40% from its IPO price, now trading on ~3x sales. Uber is a SaaS company no longer.

The fall in Uber’s share price doesn’t necessarily mean Uber is going to fail or that Uber is doing poorly at the moment. In our opinion, it just means Uber wasn’t correctly priced in the first place and public market investors were beginning to realise that when it IPO’d.

Low interest rates and easy money

Clearly there was a big difference in perspective between the public market investors that tanked Uber on the stock market and the private market investors who have collectively poured ~US$20 billion into Uber during private funding rounds between 2010 and 2018. Notable late stage Uber investors include Toyota, Softbank, fund manager Tiger Global, and Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund.

An interesting question is why late stage private market investors were so willing to put so much money into this mega unicorn with mega losses? Other companies such as WeWork and Lyft fall into this category too.

The global low interest rate environment might be a culprit. Companies will invest in projects with a lower expected return, since the hurdle is lower. The search for yield is also likely to drive floods of money into high risk/high return investments, such as venture capital, as investors can’t get an acceptable return from safe investments like bonds anymore.

Japanese conglomerate Softbank is the most aggressive of all venture capital investors. It raised a US$100billion venture capital fund called the Vision Fund to pursue investments in growth companies and it wants to raise another US$100 billion for Vision Fund 2. (The first Vision Fund invested in Uber, WeWork and Lyft). Its strategy focuses on injecting large amounts of capital into businesses which it thinks can conquer their respective market, such as ride-sharing or real estate.

It seems like it’s not a coincidence that Softbank is based in Japan, the country that’s arguably grappling with negative interest rates and economic stagnation the most. Despite concerns about its investment strategy, Softbank hasn’t found it difficult to find funding. In September, Softbank found strong demand for its junk bond offering from Japanese retail investors, who were drawn in by the “higher” interest rates on offer (1.38%).

For Softbank’s Vision Fund, it’s interesting to look at who its investors are. Nearly half of the capital comes from Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund and a large part from Abu Dhabi. These countries have immense oil wealth and massive sovereign wealth funds. They’re focused on diversifying their economies, and reducing their dependence on oil.

Interestingly, US$17 billion of Saudi Arabia’s US$45 billion investment into the Vision Fund is in the form of preferred debt, rather than equity investment. This preferred debt doesn’t give them any upside if the Vision Fund’s investments do well, but does pay them a 7% annual coupon, a very high yield relative to what other high yield bonds are paying. While Saudi Arabia wants to ride the AI revolution, maybe they’re also chasing yield?

Will these companies survive?

Negative cash flows can’t continue indefinitely into the future. Once the company runs out of cash on their balance sheet, there are a few possibilities. They may be able to raise debt or equity from investors, which gives them more time. If raising money is difficult, they might look for an acquisition from a larger company. If it has the inclination and capital, the larger company might invest back into the operations of the acquired company. Or it may strip the acquired company’s assets down and cut costs, depending on how badly it’s struggling. If all options fail, the company will go bankrupt.

Bankruptcy seems unlikely for most of these companies we’ve mentioned. Out of all of them, WeWork looks the most in danger since it only really has one big backer in Softbank. On the other hand, Softbank has proven it’s willing to support WeWork with its recent US$9.5 billion bailout. Whether this support will continue into the future is yet to be determined.

Uber has US$11.7 billion in cash on its balance sheet, enough for at least another year at its current cash burn rate. After that, it can probably raise more debt, though it currently already has around US$4.5 billion in long term debt on its balance sheet. Importantly, at a lower valuation, Uber could be attractive to equity investors and prospective acquirers due to its strong brand, technology platform, and vast data trove. In our opinion, it’s likely to survive.

The bottom line

Valuing tech companies is complicated. When investors use SaaS valuation methods for “technology” businesses with fundamentally different business models, they’re probably overvaluing the business. At the same time, there’s a lot of uncertainty involved with valuing all high growth companies (SaaS and otherwise) and investors should be prepared for a range of outcomes.

Important! We’re sharing with you our thoughts on the companies in which Spaceship Voyager invests for your informational purposes only. We think it’s important (and interesting!) to let you know what’s happening with Spaceship Voyager’s investments. However, we are not making recommendations to buy or sell holdings in a specific company. Past performance isn’t a reliable indicator or guarantee of future performance.

The Spaceship Universe Portfolio invests in Adobe, Microsoft, Salesforce, Slack and Softbank at the time of writing.

The Spaceship Index Portfolio invests in Adobe, Microsoft and Salesforce at the time of writing.