Outline

- The term economic moat was popularised by Warren Buffett in a 1999 interview with Fortune;

- Economic moats sustain a business's profit margins over the long-term;

- Spaceship recommends the book 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy by Hamilton Helmer as the best book on economic moats; and

- Spaceship uses economic moats as part of its investment strategy.

There is one certainty in business, uncertainty.

And, as long-term investors, we think the durability of a business and its ability to protect its profits is the most important thing.

Companies which develop long-term competitive advantages through the implementation of clear strategy develop economic moats.

At Spaceship, we spend a lot of time thinking about economic moats, and if certain economic moats will strengthen or weaken in different situations.

One interesting trend we are seeing is the inverse relationship between human lifespan and company lifespan. Humans are living longer and companies are dying faster.

According to the spring 2016 Innosight report Corporate Longevity: Turbulence Ahead for Large Organisations, the average tenure of companies on the S&P500 is forecast to reduce to approximately 14 years by 2026.

To understand where we are going, it's necessary to look at the future from the fundamental building blocks of any business:

- A business's capabilities;

- The intent, abilities and capabilities of its competition;

- The wants and needs of its customers;

- Value to shareholders and investors; and

- A business's pricing power.

At any point in time, a business can try to improve its strengths, mitigate its weaknesses, eliminate competitor risk, better serve its customers, maximise shareholder value, or take advantage of potential pricing power.

But there are few times where a business can do all six. This is where strategy becomes increasingly important.

A few well-known situations which created immense shareholder value include:

- IBM's move into mainframes;

- Microsoft's move into application software; and

- Apple's move into smartphones.

These opportunities were steeped in uncertainty including uncertainty of customer interest, market opportunities, success and future growth.

Prior to embarking on these projects, each company looked much smaller than they really were. These companies weren't building what already existed, they were building for what was coming, innovating on behalf of the customer.

Each of these decisions created their markets in times of immense uncertainty but the risks paid off, and now represent hundreds of billions of dollars in value for the companies and their shareholders today.

In April 2007, Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer told USA Today that "There's no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share. No chance. It's a $500 subsidised item…"

He wasn't alone. BlackBerry co-CEO Jim Balsillie apparently said "It's OK–we'll be fine". Jim assumed Apple's rise would be stunted by the iPhone's poor battery life and sub-standard digital keyboard. Both of which, were substantially improved on each new model.

Fast forward to today and Apple’s products are market leaders and the Windows Phone and BlackBerry are almost forgotten.

Apple knew something no one else did.

Hidden secrets

At Spaceship, our favourite thing to do is find investments that not many people agree with and are outside of mainstream investments. We believe the best investments are ones where we believe the consensus is wrong and have a strong conviction that we are right. This paired with great business strategy and a strong economic moat is what we call a wonderful company

As mentioned earlier, economic moats are barriers which protect a business's profit margins from the erosive forces of competition. Microsoft's Windows and Office suites are economic moats, as are Apple's vertical software and hardware integration paired with Apple's App Store. The most important thing to understand is it doesn't matter how good a product is, if the business selling it has no economic moats or competitive advantage, its competitors may just pop up and steal their profits over the long-term.

It was Warren Buffett who popularised the term moat in a 1999 interview with Fortune (which is worth reading in full):

"The key to investing is not assessing how much an industry is going to affect society, or how much it will grow, but rather determining the competitive advantage of any given company and, above all, the durability of that advantage. The products or services that have wide, sustainable moats around them are the ones that deliver rewards to investors."

A lot of technology investors tend to reduce economic moats to network effects (and for good reasons, some of the best companies in the world are built on the back of strong network effects) but there are other simple, powerful moats to look for. We think Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway is a portfolio full of them. (See Coca-Cola's brand or Apple's switching costs.)

7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy

The tech industry has a huge emphasis on execution and often ignores strategy but we think both are as equally important as each other.

The best book on economic moats isn't by Buffett but by the less popular Hamilton Helmer.

A few other people who endorse Helmer’s book include but are not limited to:

- Netflix CEO and Co-Founder - Reed Hastings;

- Spotify CEO and Co-Founder - Daniel Ek;

- Entrepreneur and investor - Peter Thiel;

- Former CEO of Adobe - Bruce Chizen;

- Stripe CEO and Co-Founder - Patrick Collison; and

- Chairman of Sequoia Capital - Mike Moritz.

We highly recommend reading 7 Powers in full if you find this post interesting. Helmer does a far better job than we can.

Power 1: Economies of Scale

Economies of Scale are straightforward but often overlooked.

The most important thing to understand is if a business has a fixed cost base, it can benefit enormously from scale.

This leads to companies trying to get big fast not because of scale itself but because being the biggest is the best way to protect their profits.

Helmer uses Netflix as an example and their pivot towards developing their own original content. I personally think Redef has the best deep dive into why originals are important to Netflix, made up of four parts (1, 2, 3, 4) but we will outline the general idea here.

Prior to making their own content, Netflix had to negotiate the rights to each TV show or film on a case-by-case basis often with multiple deals and changing terms across geographies. This is part of the reason why US Netflix and Australian Netflix are so different

Netflix was at the mercy of its suppliers (never a good place to be) who could charge a variable fee based on the number of subscribers Netflix had. This means scaling could be a bad thing.

With originals, Netflix is paying a flat fee divided across its global subscriber base who will all be able to access the same content, on the same day, regardless of where they are located.

And Netflix never has to pay another cent once the content is made.

The more subscribers the company amasses and the higher it can push its pricing, the more content it can produce – which in turn drives more subscribers, more engagement and more pricing power. This flywheel is endemic to SVOD, but unique in the history of television. Linear television networks have always been bound by a finite number of primetime slots and the size of the total primetime audience. Accordingly, a network with 15 viable slots would only add a new show (say #16 or #22) if it replaced one of its existing 15; the only thing that matters is relative outperformance. Netflix faces none of linear’s limitations – any series that can meet the company’s target cost per hour watched contributes to its penetration and engagement (as do those that don’t, albeit less efficiently).

Source: Netflix Isn't Being Reckless

The thing is, it is a bit of a chicken and an egg problem. Netflix needed to get big enough that it made sense to make its own content rather than lease from others but it needed the content from other providers to acquire to get big enough.

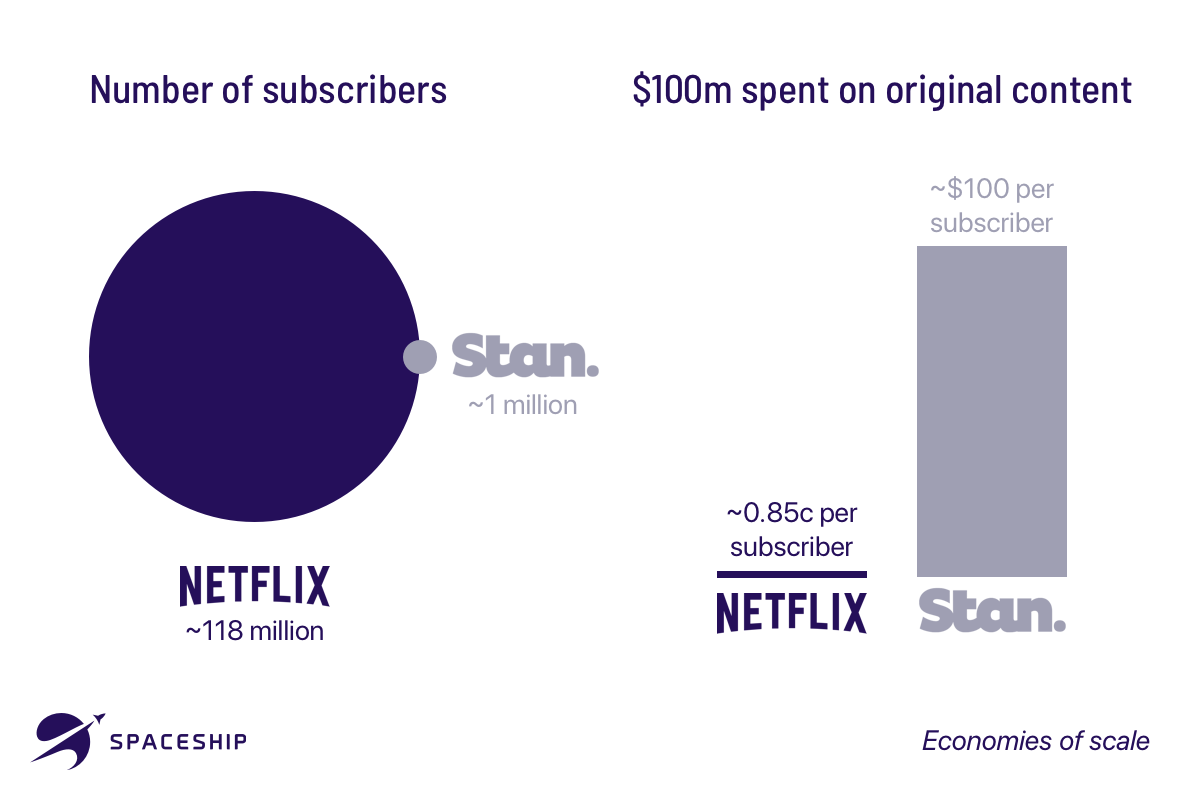

Here is why scale matters. Netflix has ~118 million subscribers and spreads the cost of an original across all of them based on their varying subscription levels. Now contrast that to Stan which has ~1 million subscribers.

If both companies want to produce an original with a budget of $100 million. Netflix will charge this cost out at ~85 cents per subscriber (100/118) and Stan will charge this cost out at $100 (100/1) per subscriber. That means in relative value, Netflix would develop more original content for less cost per subscriber allowing it to spend additional funds on marketing, a better user experience and hiring more people.

Power 2: Network effects

If you're interested in technology, there is a good chance you already understand network effects. It is one of the most important concepts for many successful technology businesses like PayPal, Facebook and Twitter.

That said, a lot of people muddle up virality and network effects because they are often seen together (but don't necessarily have to be). You can be viral without having a network effect and vice versa.

Virality isn't an economic moat but network effects are.

The simple definition of a network effect is a business that improves as it gets more customers. See Jason's post on network effects.

The simple example is Facebook.

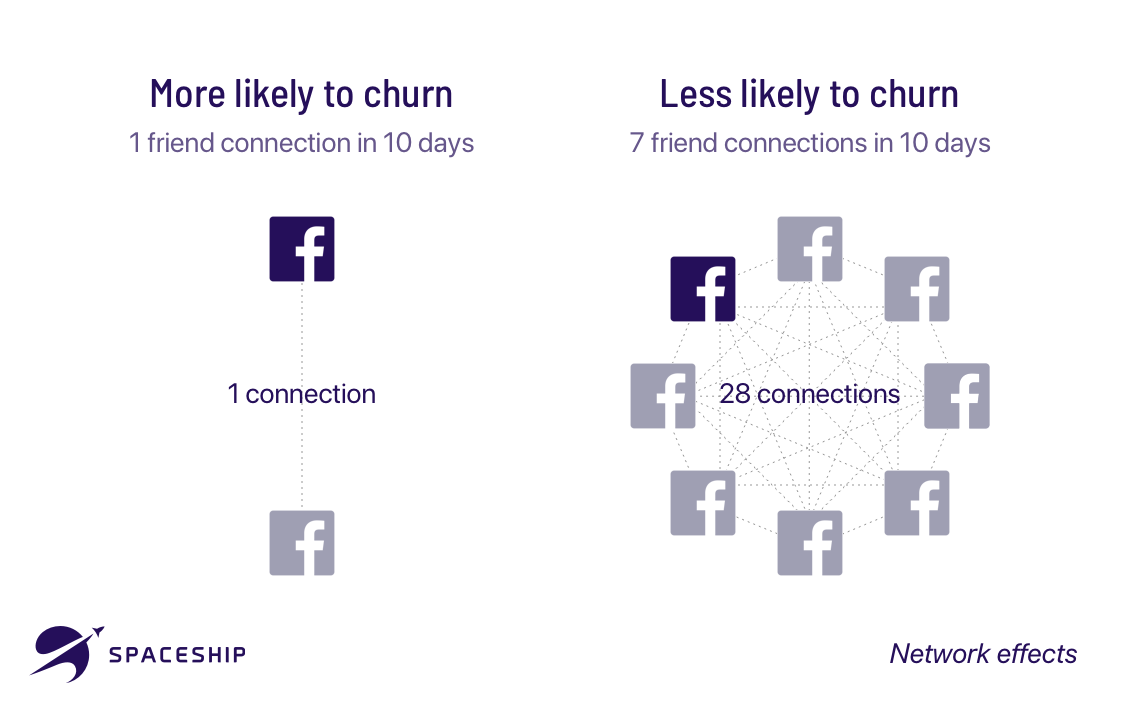

We all use Facebook because we all use Facebook. Again, it's a chicken and egg problem which is why Facebook's major focus at the start was to get each user to 'friend' 7 people in 10 days.

Once you had 7 friends you were much less likely to churn and thus added to the value of Facebook's network.

The Facebook growth team built the entire Facebook product experience to get users to friend 7 people in 10 days.

Going back to virality, virality means each user that signs up tends to invite more users. There are many examples of this on the Facebook platform itself where games go viral and quickly decline in popularity again because additional users provide no additional value.

Businesses can be viral and not have a network effect. This is dangerous because the virality can disappear and churn can eat away at the user base.

We highly recommend diving deep into network effects by reading this a16z deck and listening to Anu Hariharan from Y Combinator (who wrote the a16z deck prior to moving to Y Combinator).

Power 3: Counter-positioning

Counter-positioning is when a new business adopts a new, superior business models that incumbents can't mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business.

It's similar to Clayton Christensen's disruption theory, with less of an emphasis of moving from the lower end of the market to the upper end.

Helmer uses Kodak and their failure to adopt digital cameras as his example.

If you think about Kodak, they were best positioned to be the leader in digital cameras, after all they had expertise in film cameras.

But what Helmer (and Christensen) offer us is an opposing explanation – a contrarian point-of-view.

The reason Kodak didn't react was precisely because of its expertise and its existing business model.

Kodak as a business was set up to profit from selling film cameras that needed a new supply of film and services like film development.

Like any new technology, digital cameras looked like toys in the beginning. Film cameras were higher quality and the professionals (who were Kodak's bread and butter) weren't using digital cameras.

But as Aaron Harris says in Toy Markets:

Investors should know how important it is to bet on toy markets. They’re the ones who have learned, again and again, that the biggest companies start out looking like toys. Amazon was for selling books online when relatively few people used the internet. Google was a search engine in a landscape crowded with search engines that weren’t themselves gigantic businesses. eBay was for selling beanie babies.

Disruption was coming in two forms – business model and changes in technology.

Digital cameras didn't need film and the photos didn't necessarily need to be develop, at least not in the way that Kodak developed film.

If Kodak were to develop a better digital camera, they would be eating away at their own profits rather than a competitor's.

The most important thing to understand is things that look like toys improve and often become good enough even for professional users.

In our opinion, Kodak management probably knew this.

Put yourself in the shoes of Kodak's management.

Do you take money and your best people away from what makes you money (film) to work on something that will likely make you far less in the future (digital) when your customers aren't currently using it?

Or do you keep milking what you've got until it's gone?

For most managers who are paid by last quarter performance – you can see what they'd go for (this is why, at Spaceship Capital, we like portfolio investments in companies which have high equity ownership).

One thing Kodak's management probably didn't realise is how digital cameras (and eventually smartphones) would make everyone a photographer.

Power 4: Switching costs

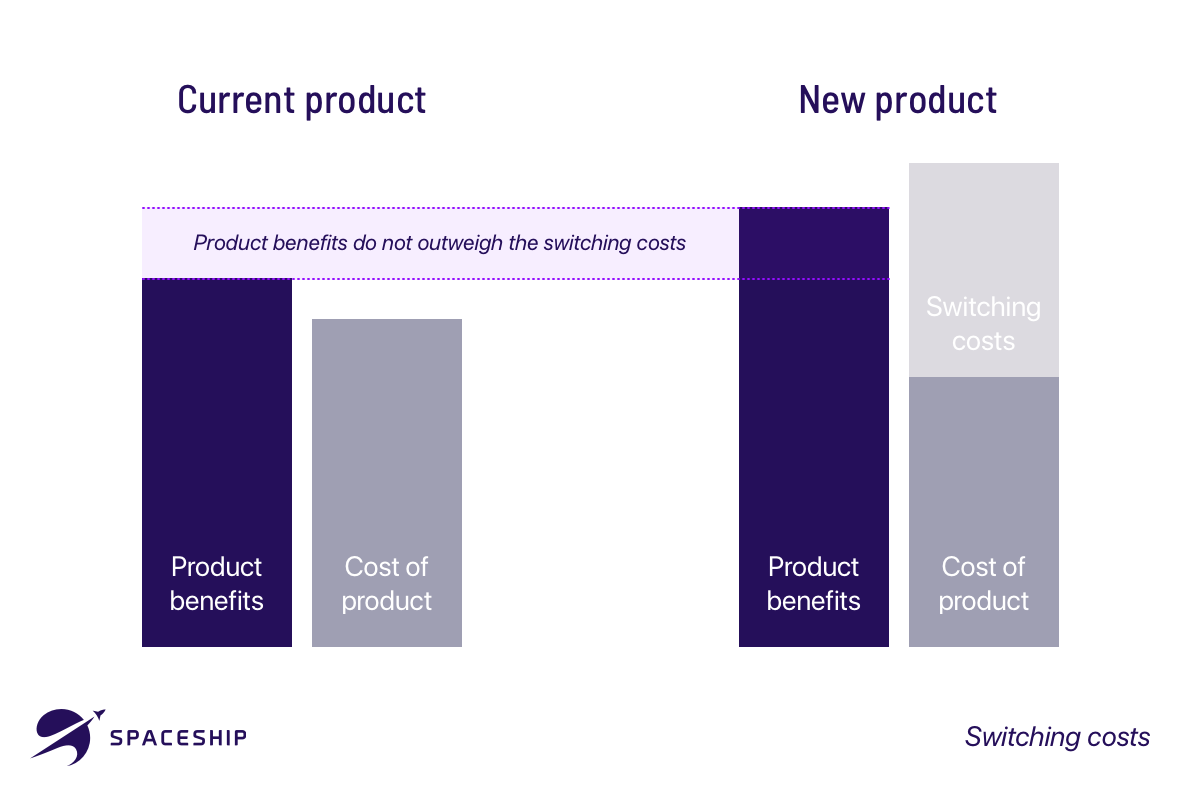

Switching costs are when it's easier for a customer to stay with a product or service than it is to switch (even if the new product is objectively better)

Switching costs lock in customers and additional products, features, integrations, consulting, and training can deepen them and make it even harder to switch.

This is a big reason why many companies will provide universities with free access to their software to teach students. It means when they get to the workforce they have already learnt software and would incur switching costs when learning a competitor’s software.

Helmer uses the example of SAP, which over time can become the backbone of organisations, but we think Adobe and Salesforce are better examples.

Once you learn the Creative Cloud and Analytics Cloud suites from Adobe or learn Salesforce's cloud platforms it's often not worth switching platforms or software as it can take months to retrain your workforce and set up the business logic on a new platform.

Switching costs are never huge for a single person but when an organisation has thousands of users of a certain platform, it can mean thousands of hours of productivity lost.

Even if a new solution is 10% better, it may not make sense to switch.

This is a big reason for vendor lock-in and why enterprise software can be terrible, overpriced, and have bad UX – and still succeed.

Other reasons include:

- The person who uses the software is not the person buying the software. Managers prefer to go with the tried and tested rather than something new that may be better – they don't want to risk their reputation on a new shiny solution.

- The software is optimised for compliance, complicated workflows, permission management, etc and the user experience takes a back seat.

- No one is in charge of re-evaluating the old software solutions, so companies just keep paying for what they have.

Power 5: Branding

Brand is arguably the most powerful and least understood of the 7 Powers. It's so durable because of how complicated and time intensive it is to build a brand.

If you look at Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway portfolio you see a lot of powerful brands, to name only a few:

- American Express;

- Wells Fargo & Co;

- Apple;

- Heinz;

- General Motors;

- Coca Cola;

- See's Candy;

- Duracell;

- Bank of America Corp;

- Goldman Sachs;

- IBM; and

- Johnson & Johnson.

There's many more, see here if interested.

What we find interesting is many of the world's biggest brands sell commoditised goods. There is nothing different between them and their competitors beyond the company or product name.

But what customers are paying for is a consistent experience and years (even decades) of consistent messaging.

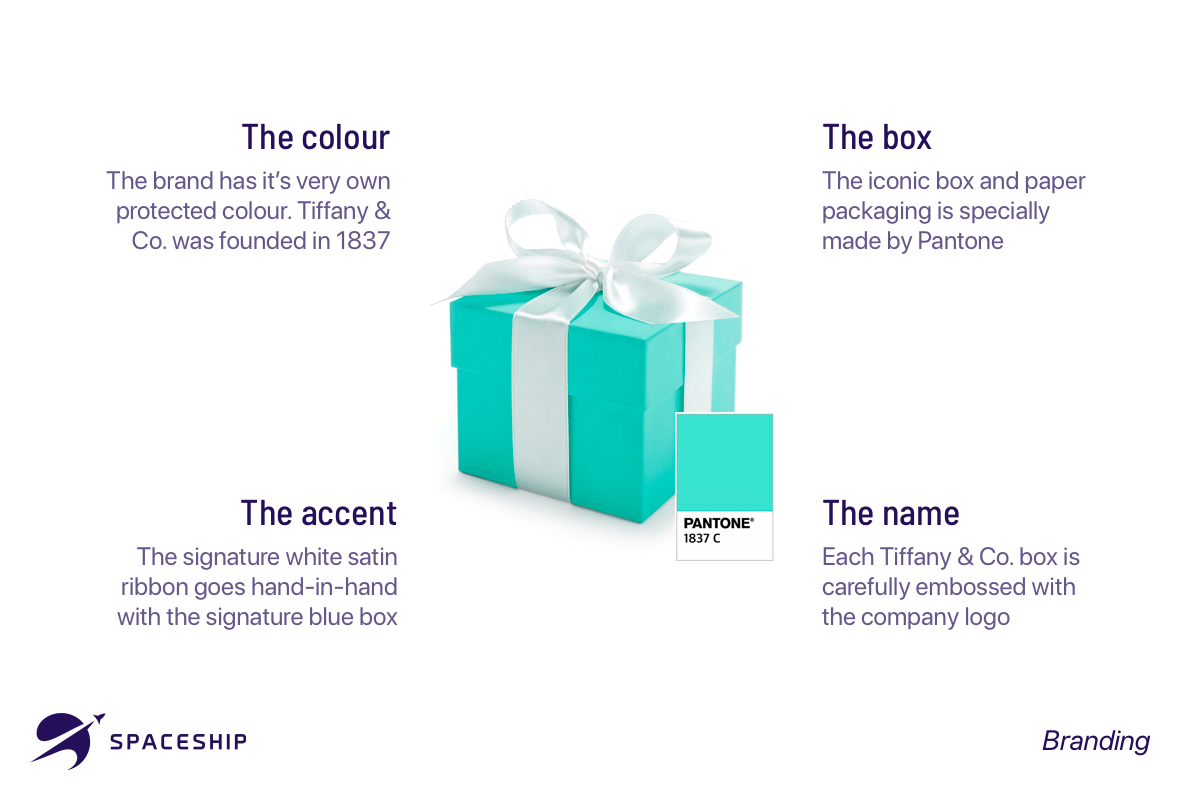

The best example is Tiffany & Co, the American luxury jewellery retailer. This brand is so strong people want to buy used Tiffany's boxes on eBay.

When Tiffany's introduced its diamond engagement ring in 1886, the Tiffany Blue Box became as desired as what was inside.

You're not buying a diamond ring, you're buying a Tiffany's diamond ring and over 100 years of consistent advertising that says when your partner buys you Tiffany's they love you and that there is no replacement for the Blue Box.

Brand is an incredibly powerful feedback loop, the more people who know the brand, the more they expect to see it, and the more people want it.

In the past, the Blue Box meant better placements in malls and the store itself acted as a channel for people to discover Tiffany's.

One important thing to understand is the Internet may be changing how brands develop and how powerful brand is as an economic moat.

You only have to look at the rise of Airbnb surpassing the likes of Hilton and other hotel brands.

Placement and brand aren't as important on the Internet's infinite mall with unlimited shelf-space, and near zero cost of distribution meaning new ways to build brands.

Reaching millions isn't as hard as it used to be thanks to Facebook and Google.

Power 6: Cornered Resource

A company has a cornered resource when it has preferential access to limited resource or labour force.

A good example for talent is Amazon, who according to The Information, have a 17-person senior leadership team, called the S-team, who have an average tenure of 15 years – the majority of the company's 23 year lifespan.

The S-Team have more context than almost anyone else at the company and it's extremely rare for a technology business to have a team stick around for 15 years. It’s unlikely there is any team in the world with more context and understanding about ecommerce than the S-Team.

Other famous examples:

- Apple's design team led by Jony Ive;

- The PayPal Mafia; and

- Pixar's Braintrust.

Power 7: Process Power

Process Power is when an organisation and its activity sets enable the offering of lower costs and/or superior products to consumers.

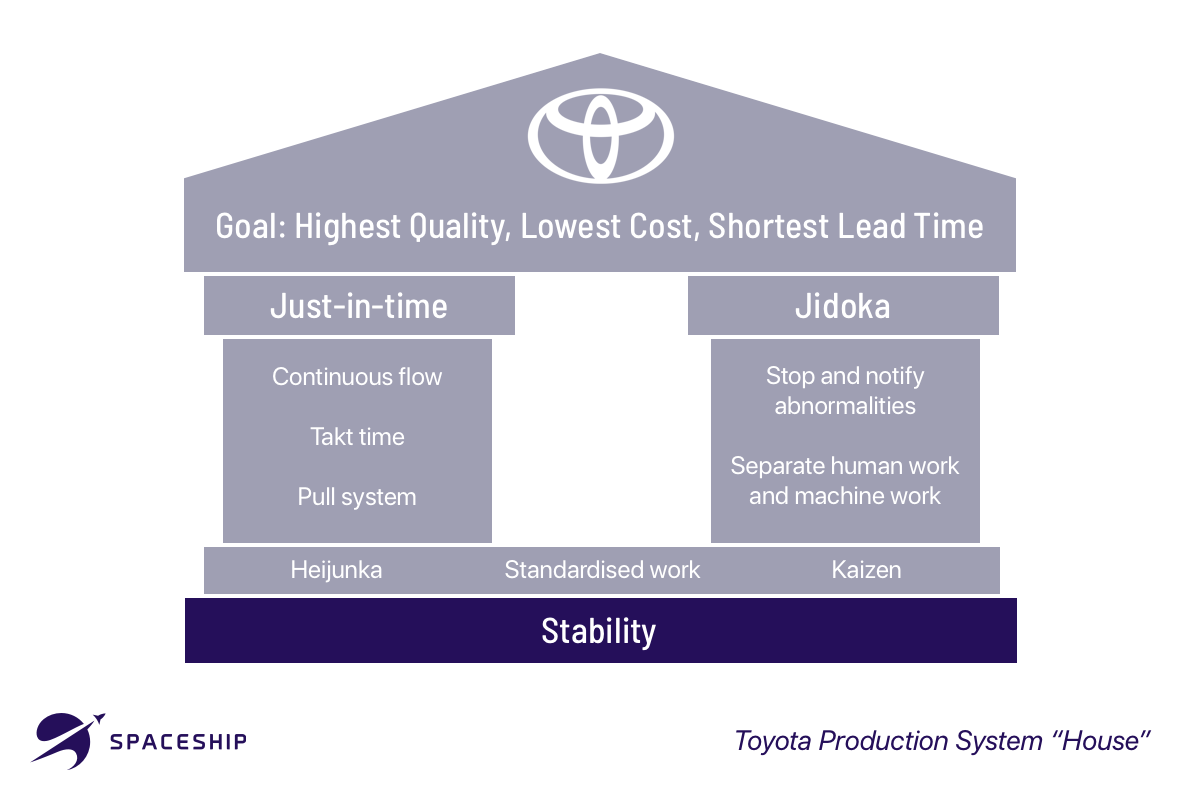

Process Power is one of the hardest powers to copy, Toyota is famously transparent about its processes but other companies haven't been able to reach its operational excellence.

Toyota use a Kanban just-in-time manufacturing system where any worker from Janitor to CEO can stop the production line if they see something dangerous or something that could be improved.

Toyota gave tours and created a joint venture with GM training workers in Japan but the joint venture still couldn't replicate the Process Power of Toyota's Japanese factories.

The most important thing to understand is Process Power isn't built on checklists, it's embedded in the organisation – in its culture.

Insiders learn it by osmosis and it all feels natural to them.

To outsiders, it all looks like magic – and it sort of is.

Other good examples of Process Power are Instagram and WhatsApp, both were worth billions of dollars with less than 60 full-time employees, 13 employees for Instagram and 55 employees for WhatsApp.

The Path to Power

Each Power comes from invention.

Businesses create something new and produce substantial, sustainable economic gains.

Look at how Netflix established its power (after DVDs).

SVOD was an attractive new service which led to sign ups and eventually scale. That scale is now being leveraged to develop originals, exclusive and fixed cost programming and to reduce variable costs.

Over time, we may see Netflix develop a powerful Brand and Process Power around their original programming too.

Don't limit these seven mental models to companies. They apply to individual careers too that could be experienced in a scaling business, having a big network, a pair of uncommon skills, a great personal brand, being part of a cornered resource, or being a great process person.

What we take from 7 Powers is it's as important to decide what to work on as it is to work hard. Netflix would never have become Netflix without economies of scale and counter-positioning.

Netflix had to be different and right.

We recommend pairing 7 Powers with Superforecasting and Expert Political Judgment by Philip Tetlock, Thinking in Bets by Annie Duke, and The Book of Why by Judea Pearl.