Life as we know is only a few hundred years old. Capitalism has changed our lives, and part of economics is attempting to understand how capitalism and other economic systems work. If capitalism isn’t your thing, we’ll touch on far more in this series. This is the beginning and we believe it’s a good place to start to provide a contextual framework. Economics has many umbrellas, like behavioural economics, and both microeconomics and macroeconomics. Through this series, we will touch on all of them at some point.

For now, I think the best place to start our economics journey is with history.

For the last 300 years, we’ve seen an increase in the average standard of living, year on year, but it hasn’t always been like that. We take it for granted that our economy has (for the most part) grown year on year for our entire lifetime, our parents’ lifetime, and their parents before them.

Economic growth is measured by an increase in the amount of goods and services produced over a period of time. The more growth we see, the more we produce as a society.

However, for over a thousand years, we didn’t really progress, at least not in economic terms. So what happened that changed that? And can we really take growth for granted? In Economics 101, we’re going to try answer those questions and more.

We believe, along with many economists, that economic growth is associated with the introduction of capitalism and the ensuing free market economy. The rise of capitalism brought notions of property, pricing and the invisible hand to the main stage.

Today, advances in technology and deep specialisation are fundamental to increasing productivity. Productivity is a measure of output (i.e. revenue or components of GDP) per unit of input (i.e. labour or capital). Another representation of this is the amount of goods and services one person produces over a set period of time. If you’re a chef, that’s the food you make and sell. This has generally led to continuous increases in living standards, and that’s a great thing. People desire to live a better life, but we’ve also seen increasing threats to our environment, and growing inequality. The rich get richer, and the rest of us keep working. Through our Economics 101 series, we want to give you the tools to think about our capitalistic world and maybe, just maybe, get ahead of the average.

If you’ve never studied economics. Don’t worry. Think of economics as the study of how people interact with each other, and their environment, in order to produce goods and services that enable them to live, and hopefully, prosper.

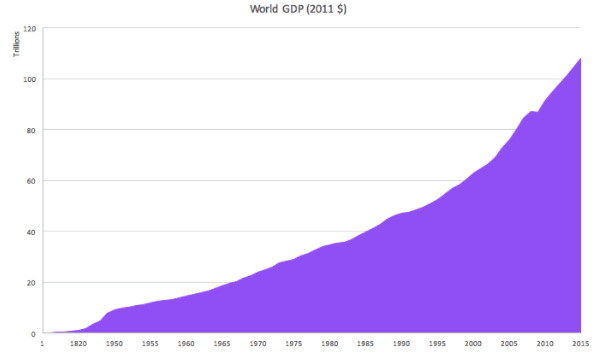

We’ll make it as approachable as we can. Below is an area graph showing the change in the world’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 1 to 2015. GDP is the total amount of goods and services that are produced in a country over a year. So, the world’s GDP is what is produced by every nation. As you can see, there wasn’t really any growth in GDP until the 1700s, then we started to produce more and more each year. From 1 to 1501, the world’s output pretty much stayed the same. That’s almost unthinkable for us sitting here in 2017.

It’s worth stopping and thinking about that for a second. Despite what financial analysts and the news tell you about how the economy must grow, it’s still a relatively new phenomena. We’re really still at the beginning of understanding what it means to grow and whether it’s a permanent fixture or the last three hundred years was unique.

For most of human existence, the most important thing was whether we had enough food and somewhere safe to sleep. If you’re reading this, you’re probably good in both those departments. The fourteenth century Moroccan Ib’n Battuta once said, when talking about Bengal in India, ‘A country of great extent, and one in which rice is extremely abundant. Indeed, I have seen no region of the earth in which provisions are so plentiful.’

He’s not talking about the importance of education or the ability to access capital to make money. He’s talking about food. Countries weren’t really richer or poorer than one another, at least not like today. Sure, you may have been better off in China or England than somewhere in Africa. But the real difference was between the rich and the poor. Especially in feudal countries were the ruling elite may have quite literally owned their people.

Unlike today, where you were born didn’t matter as much as what family you were born into.

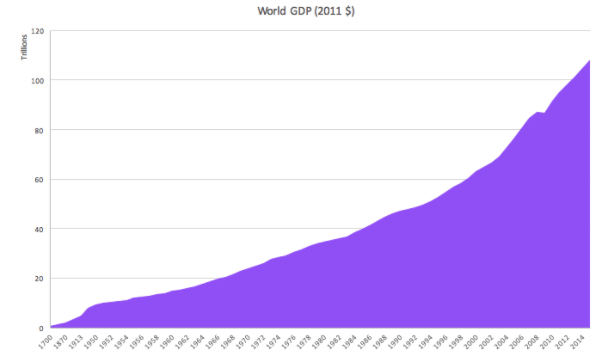

Fast forward a few hundred years to the Industrial Revolution where the era of economic growth in capitalist economies began. Many historians believe the Industrial Revolution was the most important event in the history of humanity since we domesticated animals and plants. It was really the first time mechanical muscles replaced humans and animals, and people began to specialise and sell their goods and services to other people, rather than producing all they needed for themselves.

While the precise start to the Industrial Revolution is heavily debated, let’s say it started in 1700. See the below graph, the same as above except it starts at 1700 rather than 1. As you can see, this is when people started to obtain income by producing and selling goods and services, measured as an increase in GDP.

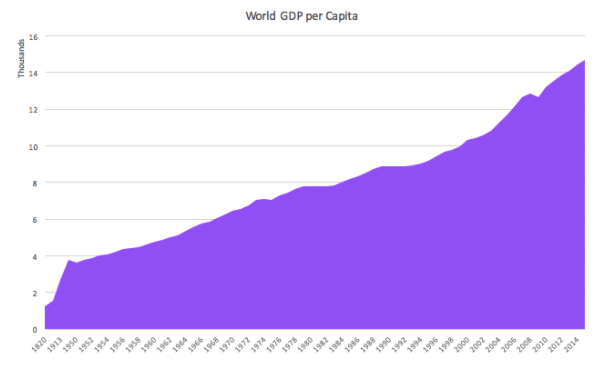

Fast forward to today, despite having two world wars, the average person is a lot better off than ever before. One way to measure that is by GDP per capita. Recall, GDP is the total amount of goods and services produced over a year. So, GDP per capita is how much the average person produces each year. Below is a graph our world GDP per capita from 1820 to 2015.

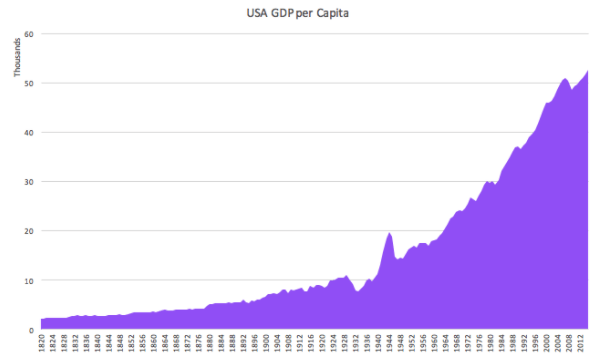

I think it’s important to point out that from 1820 to 2015, we’ve seen world GDP per capita increase from nearly $2,000 to just under $15,000 or in other words, the average person produces 7.5X more than they did 300 years ago. Keep in mind, this is skewed by poorer countries who haven’t seen the same economic growth that countries like the United States has. See below for the GDP per capita growth in the USA over the same period, it has a big more fidelity than the above graph, so it gives us a better look into how capitalism and the Industrial Revolution affected the United States.

As you can see, averages aren’t always the best way to show change. The US has seen an increase from just over $2,000 in 1820, just above the world average, to over $52,000 in 2015. That’s a 26X increase in GDP per Capita in the US versus a 7.5X increase worldwide. The average person in the United States produces 3.4X more than the world average in terms of GDP per capita. Keep in mind, some groups would have seen much larger increases and many much less. Averages aren’t everything.

The interesting thing about comparing world to the US is that they both started at around the same place. So, what made the US far more successful?

That’s what we’ll try to explain in our Economics 101 series. Data is the starting point of economics and we’ll make it approachable and easy-to-understand. If anything isn’t clear, let us know and we’ll update it.

As a quick recap of what we’ve talked about so far:

- Capitalism;

- GDP;

- The Industrial Revolution; and

- Why averages aren’t everything.

To end, I leave you with three quotes from Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, food for thought:

“The capitalist and consumerist ethics are two sides of the same coin, a merger of two commandments. The supreme commandment of the rich is ‘Invest!’ The supreme commandment of the rest of us is ‘Buy!’ The capitalist–consumerist ethic is revolutionary in another respect. Most previous ethical systems presented people with a pretty tough deal. They were promised paradise, but only if they cultivated compassion and tolerance, overcame craving and anger, and restrained their selfish interests. This was too tough for most. The history of ethics is a sad tale of wonderful ideals that nobody can live up to. Most Christians did not imitate Christ, most Buddhists failed to follow Buddha, and most Confucians would have caused Confucius a temper tantrum. In contrast, most people today successfully live up to the capitalist–consumerist ideal. The new ethic promises paradise on condition that the rich remain greedy and spend their time making more money and that the masses give free reign to their cravings and passions and buy more and more. This is the first religion in history whose followers actually do what they are asked to do. How though do we know that we'll really get paradise in return? We've seen it on television.”

“You could never convince a monkey to give you a banana by promising him limitless bananas after death in monkey heaven.”

“How do you cause people to believe in an imagined order such as Christianity, democracy or capitalism? First, you never admit that the order is imagined.”